Google investor snaps up 'game-changing' solar innovation

Venture capitalist Alberto Chang-Rajii has invested $1.5 million in a research partnership with UNSW engineers to commercialise a new generation of 'paint on' solar cells.

Venture capitalist Alberto Chang-Rajii has invested $1.5 million in a research partnership with UNSW engineers to commercialise a new generation of 'paint on' solar cells.

Steve Offner

UNSW Media Office

9385 1583 or 0424 580 208

s.offner@unsw.edu.au

A low-cost, high-efficiency solar cell that can be 'painted' onto building tiles, windows and car roofs, has attracted $1.5 million in seed funding from a top international investor.

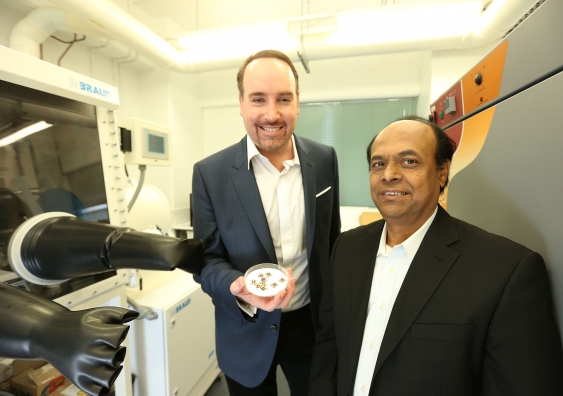

Private equity investor Alberto Chang-Rajii, who made the announcement while visiting UNSW, knows a thing or two about identifying “game-changing” technologies and getting in early.

While completing his MBA at Stanford University in the mid-90s, he scraped together $10,000 to purchase 1% of a little-known start-up called Google. His share in the internet giant is today worth an estimated US$3.74 billion.

A career venture capitalist, he now operates a global private equity firm Grupo Arcano, based in Chile. The firm invests in energy, technology, and financial services companies, and in 2014, it expanded its operations to Australia, where Chang-Rajii says he plans to invest upwards of $100 million over the next two years.

He recently kicked off that spree by announcing his first Australian investment – a $1.5 million research partnership with a team of photovoltaic (PV) engineers from UNSW, through a spin out company called Future Solar Technologies.

The research, which is led by UNSW engineer Ashraf Uddin, is developing next-generation solar cells made not from silicon, but from hybrid perovskites.

In the last 24 months, this super-cheap material has taken the global PV research community by storm.

An editorial titled ‘Pervoskite Fever’, published in the journal Nature Materials in late 2014, said hybrid perovskite was “exceptionally promising” and “may revolutionise the field of renewable energy.

And MIT Technology Review has suggested it could offer “dirt cheap” solar power.

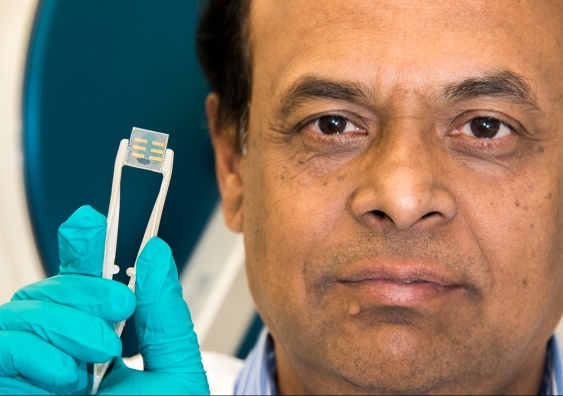

UNSW's Ashraf Uddin with one of the next generation hybrid perovskite solar cells. Photo: Robert Largent

Uddin says his team is targeting greater than 20% conversion efficiency rates for its cells within three years – more or less on par with mass-produced silicon solar cells.

And while the lifespan of these next-gen solar cells is shorter, they offer some very clear advantages over conventional rooftop panels. They are significantly thinner, lighter and more flexible, which means they can be easily applied to a range of different surfaces, such as exterior walls and windows, transport vehicles, and even mobile phones.

“You can laminate a two-bedroom house so it becomes a zero-energy house, and it would only cost about $2000,” Uddin told The Australian Financial Review.

But the low-cost to produce his paint-on solar cells was the ultimate draw card for Chang-Rajii, who says it doesn’t matter how good the science is “if it’s not accessible to everyone”.

“If it’s the cure for cancer and if it costs a billion dollars it’s not a cure, it’s a luxury.”

Although the technology is still in the early stages of development, Chang-Rajii sees enormous potential.

“I’m not investing in a tiny microscopic cell in a lab, I’m investing in the future homes that will not require energy because their tiles will be photovoltaic panels,” he says.

This is “world-scale” technology that “can reach everyone”, he says. “It will change the way we build and use electronics. It’s a game-changer.

“We consider ourselves successful, not only if we make money, but if we see the product in people’s lives,” he added.

The Chilean investor is not exactly new to the solar industry. His investment firm previously owned part of Solar Chile, a major solar farm developer in the Atacama Desert, but sold the company in 2013, earlier than planned, to US-based First Solar.

“They bought us for a large amount of money, so we couldn’t say no,” he says, with a laugh. “But there was so much I wanted to do with solar energy.”

So he started doing some research, and was soon drawn to UNSW because of the stellar reputation of Martin Green – a Fellow of the Royal Society who many consider the ‘father of photovoltaics’.

Chang-Rajii, through his Sydney office, made contact and learned about UNSW’s research into perovskite solar cells.

His company’s technology team was simultaneously hearing presentations from solar engineers at Oxford University and UCLA, but he says “nothing was as interesting” as the UNSW research.

Sweetening the deal was UNSW’s Easy Access IP scheme, which is designed to streamline investment opportunities by awarding patent-free licences for companies interested in further developing UNSW research.

Under this innovative program, UNSW granted Chang-Rajii and Future Solar Technologies a free licence for the patent that already existed, as well as free access to any patents that are subsequently filed by the same research group.

Chang-Rajii says his investment firm often collaborates with universities because “it’s where you get the brightest minds, the best projects, and the lack of funding, so it’s where we can be of assistance.”

“Usually one of the hardest conversations with other institutions is the IP – because at the end, it’s what holds the knowledge.

“I think there is no other institution currently that we’ve had the pleasure to work with that has been so generous, easy to work with, fast, and open-minded about investing and the result of it,” he says of UNSW.

Although he admits he “doesn’t always pick winners”, the venture capitalist has a very good track record.

Before teaming up with UNSW, his three most recent investments were with high-profile companies including the electronic payment system Square, the photo messaging app Snapchat, and the taxi-replacement app Uber.

“All the things I invest in have a common trend,” he says. “In their own way they are disruptive … they bring innovation, they are global, they can escalate, and they are very easy to explain.”

This last point is Chang-Rajii’s “golden rule” governing all investments.

“If someone cannot explain me a business in less than 60 seconds without a pen, paper or PowerPoint, I don’t invest,” he says.

“If they have to repeat it, or I have to ask, I don’t invest.”

It’s a glimpse into the cutthroat mentality of a successful venture capitalist, but it also speaks volumes about the people who leave an impression, and ultimately, get him to open his wallet.

Ashraf Uddin is one of those people.

The UNSW solar engineer was in the middle of submitting grant applications for the Australian Research Council when he first spoke with Chang-Rajii. He says he made a compelling – albeit brief – pitch to the investor.

He is now on a very different path towards commercialising his “game-changing” solar technology – and he’s got some heavyweight support backing him up.

Read the story in The Australian Financial Review.