Without the faces of men

The facial disfigurement of Great War veterans led one researcher to uncover stories that challenge our ideas of the sacrifice of war.

The facial disfigurement of Great War veterans led one researcher to uncover stories that challenge our ideas of the sacrifice of war.

Research inspiration can come from anywhere. For Kerry Neale it came during a 2006 talkback radio program on World War I, when people rang in to tell stories of relatives who had fought in the Battle of the Somme.

“One man talked about his grandfather, who had suffered horrible facial injuries and lost his nose,” Neale says. “He had endured various reconstructive operations during which close-up photos were taken of his face. The man said, as the operations progressed, you could see in the photos how his grandfather’s eyes began to lose their spark for life.”

At the time Neale found the account difficult to understand. After all, the man’s face was being repaired, so why the gloomy reaction?

Drawn to discover more about the experiences of disfigured Great War veterans, Neale made it the focus of her PhD within UNSW Canberra’s School of Humanities and Social Sciences. She began with medical records of more than 4,000 Allied soldiers treated for facial wounds at the Queen’s Hospital in Kent.

“Some of the photos are quite confronting. But the more I looked at them, the more I wanted to know the story behind them,” she says.

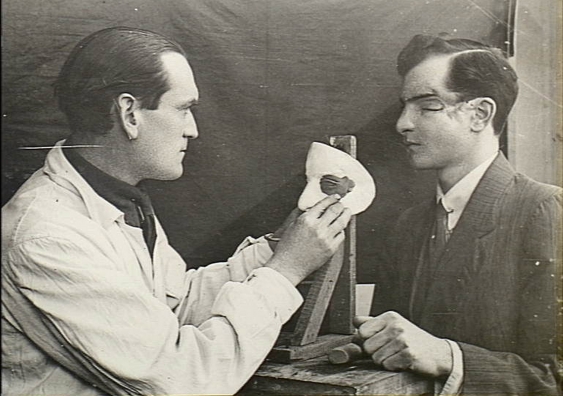

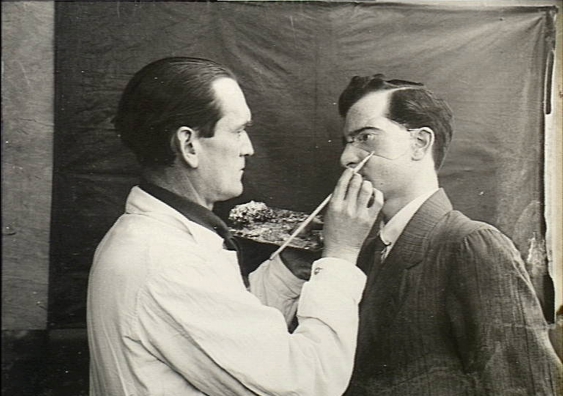

Photo: The Australian War Memorial

The veterans’ homecoming experiences have been significantly overlooked, says Neale, who is now an assistant curator at the Australian War Memorial.

“Most people associate war wounds with amputees or shellshock, but the idea of facial disfigurement rarely comes up. It’s one thing to fight and even die in war. It’s another to come back with no face,” she says.

Often the medical treatments the men endured were as confronting as the wounds themselves. “Some of the techniques are still used today in plastic surgery, but the expertise and tools back then were very basic,” she says.

The social stigma of disfigurement was profound.

“The repatriation department suggested using the word ‘repulsive’ to describe the men and some of the men referred to themselves as monsters, broken gargoyles, and as being no longer human,” Neale says.

“The face is where our identity and our personality is conveyed. To be disfigured in this way was a major challenge to perceptions of manhood and the notion of the ‘patriotic sacrifice’.”

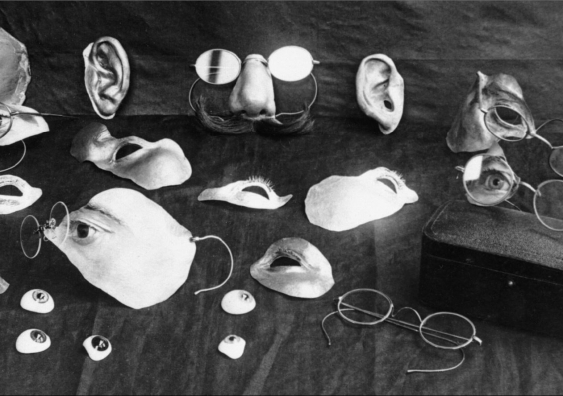

Facial prosthetics used after the war. Photo: The Australian War Memorial

Neale suggests knowledge of veterans’ experiences is important to our understanding of the effects of today’s military conflicts.

While providing far better protection than the battlefield clothing of 100 years ago, modern body armour still leaves the face exposed to shrapnel from improvised explosive devices.

“Between 17% and 20% of all wounds in Iraq and Afghanistan were facial wounds, which is actually more than the 12% to 15% in the First World War,” Neale says.

Like some veterans today, many of the wounded World War I soldiers became estranged from their families. “These days we might say they were suffering depression or PTSD. For the grandfather of the man I listened to on the radio, this was most likely the case,” Neale says.

“We have been reluctant to delve into these accounts because we assume they will be only stories of suffering and loss. But many of the men were incredibly resilient. They found jobs, went into relationships and had children. It was very much a personal journey.”

This article was first published in the Winter 2014 issue of the UNSW magazine/Uniken.